How Does Developmental Perspective Connect with Level 5 Leadership?

In the previous blog post Leadership 2050 – What Does the Future of Leadership Look Like? We referred to Strategist, also known as Level 5 Leadership, as referenced by Jim Collins in his best-selling book Good to Great. In this post, we will present the foundation of developmental perspective (one of the five key elements of the innovative leadership framework). We will start with the basics, and then, during the next five weeks, we will explore the five most common developmental perspectives. Since people grow through perspectives or levels, we will walk you through the levels ending with strategist.

In the previous blog post Leadership 2050 – What Does the Future of Leadership Look Like? We referred to Strategist, also known as Level 5 Leadership, as referenced by Jim Collins in his best-selling book Good to Great. In this post, we will present the foundation of developmental perspective (one of the five key elements of the innovative leadership framework). We will start with the basics, and then, during the next five weeks, we will explore the five most common developmental perspectives. Since people grow through perspectives or levels, we will walk you through the levels ending with strategist.

The Importance of Developmental Level/Perspective

We believe a solid understanding of developmental levels and perspectives is an important foundation for leadership development. Developmental perspectives significantly influence how you see your role and function in the workplace, how you interact with other people and how you solve problems. The term developmental perspective can be described as “meaning making” or how you make meaning or sense of experiences. This is important because the algorithm you use to make sense of the world influences your thoughts and actions. Incorporating these perspectives into your inner exploration is critical to shaping innovative leadership. We will look at the five most common of those meaning-making approaches in greater detail in this blog series.

Leadership research strongly suggests that although inherent leader type determines your tendency to lead, good leaders develop over time. Therefore, it is often the case that leaders are perhaps both born and made. How leaders are made is best described using an approach that considers developmental perspective.

The Leadership Maturity Model and Developmental Levels/Perspectives

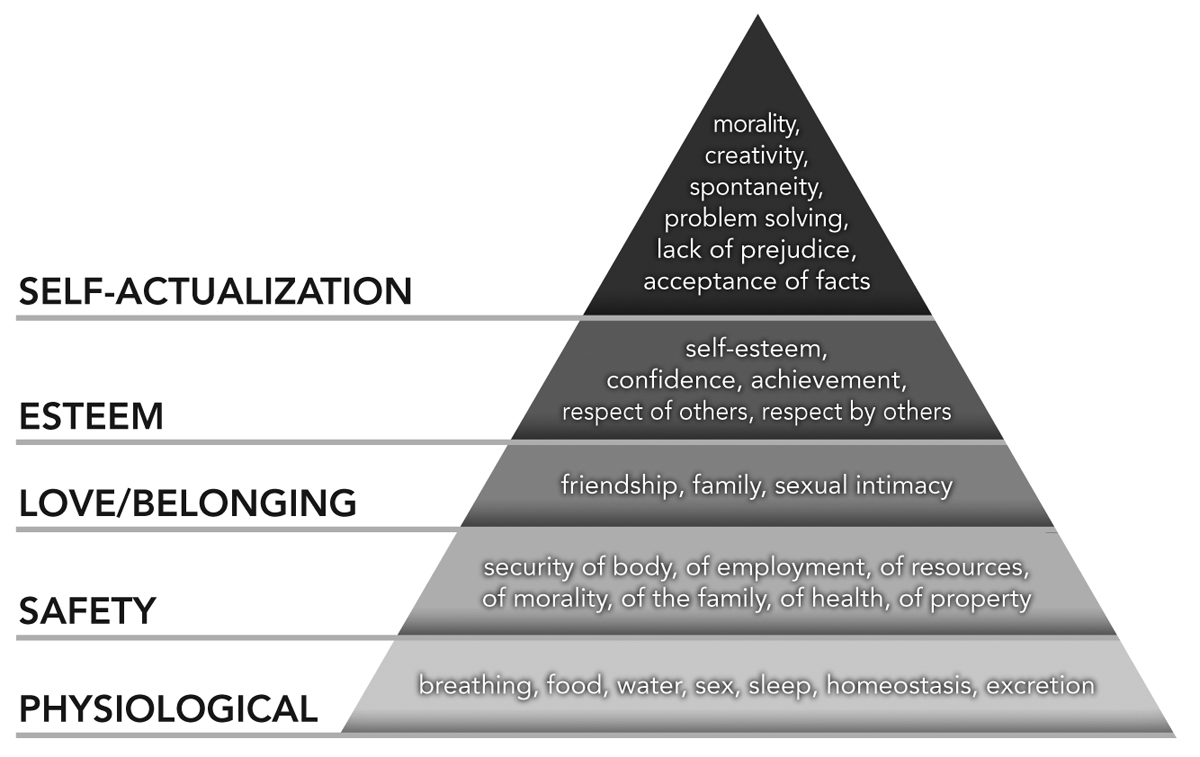

The developmental perspective approach is based on research and observation that, over time, people tend to grow and progress through several very distinct stages of awareness and ability. One of the most well-known and tested developmental models is Abraham Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs.” A visual aid Maslow created to help explain his hierarchy of needs is a pyramid that shows levels of human needs, both psychological and physical. As you ascend the pyramid’s steps, you can eventually reach self-actualization.

The developmental perspective approach is based on research and observation that, over time, people tend to grow and progress through several very distinct stages of awareness and ability. One of the most well-known and tested developmental models is Abraham Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs.” A visual aid Maslow created to help explain his hierarchy of needs is a pyramid that shows levels of human needs, both psychological and physical. As you ascend the pyramid’s steps, you can eventually reach self-actualization.

Developmental growth occurs much like other capabilities grow in your life. We call this “transcend and include” in that you transcend the prior level/perspective and still maintain the ability to function at that perspective. Let us use the example of learning how to run to illustrate the development process. You must first learn to stand and walk before you can run. And yet, as you eventually master running, you still effortlessly retain the earlier foundational skill that allowed you to stand and walk. In other words, you can develop your capacity to build beyond your basic skills by moving through more progressive stages.

People develop through stages at differing rates, often influenced by significant events or “disorienting dilemmas.” Those events or dilemmas provide opportunities to begin experiencing your world from a completely different point of view. The nature of those influential events can vary greatly, ranging from positive social occasions like marriage, a new job, or the birth of a child to negative experiences, such as job loss, an accident, or the death of a loved one. These situations may often trigger more lasting changes in your thinking and feeling. New developmental perspectives can develop gradually over time or, in some cases, emerge abruptly.

Some developmentally advanced people may be relatively young, yet others may experience very little developmental nuance throughout their lives. Adding to the complexity of developmental growth is that the unfolding of developmental perspectives is not predictably evident along the lines of age, gender, nationality, or affluence. We can only experientially sense indicators that help us identify developmental perspectives when we listen and exchange ideas with others, employ introspection, and display openness to learning. In fact, most people naturally intuit and discern what motivates others and causes some of their greatest challenges.

To further examine developmental perspectives, we will talk about the assessment tool we use, the Maturity Assessment Profile (MAP), and its conceptual support, the Leadership Maturity Framework (LMF). Susann Cook-Greuter created this developmental toolset as part of her doctoral dissertation at Harvard. We will use the MAP and the Leadership Maturity Framework as the foundation for our developmental discussion. The MAP evaluates three primary dimensions to determine developmental perspective: cognitive complexity, emotional competence and behavior.

3 Dimensions of Developmental Level/Perspective

- Cognitive complexity describes your capacity to take multiple perspectives and think through increasingly more complex problems. This is akin to solving an algebra problem with multiple variables. For example, a complex thinker can balance competing interests like employees’ desire for higher pay with customers’ desire to pay low prices and receive good service.

- Emotional competence describes your self-awareness, self-management, awareness of others, ability to build and maintain effective relationships, and capacity for empathetic response.

- Behavior describes how you act; this dimension generally describes your actions.

A sense of time, or time horizon, is another essential feature in developing perspective. For example, if a leader is limited by their developmental perspective to thinking about completing tasks within a timeline of three months or less, then optimally, this leader should only be leading a part of the organization that requires short-term tasks. On the other hand, if a leader can think and implement tasks with three-year time horizons, then that leader can and likely should be taking on a role that includes longer-term tasks. This could be a leader responsible for overseeing the implementation of an enterprise-wide computer system, where the migration may take substantially more time, and the process is more complex.

Elaborating on this example, there will be components of the team primarily responsible for the more tactical, hands-on part of the installation and who demonstrate shorter time horizon thinking. They are held accountable for certain tasks within the plan but will not be responsible for designing the more strategic portions nor be charged with the daily decisions that impact the overall budget.

Further still, imagine that one year into the project a key member of the team takes another job and the Project Manager (PM) becomes responsible for finding a suitable replacement. The PM must consider all options when selecting a replacement. The most effective staffing solution for the project will need to account for potential changes over the next several years and how they will impact overall project cost, outcome quality, and team cohesiveness. Time horizons and developmental complexity are directly applicable to innovative organizational decisions.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!