Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI) Innovative Health Care Leadership

The article was published in an Appendix to the recently released Innovative Leadership in Health Care book by Maureen Metcalf of Innovative Leadership Institute and Erin S. Barry, M.S; Dukagjin M. Blajak, M.D., Ph.D.; Suzanna Fitzpatrick, DNP; Michael Morrow-Fox, M.B.A., Ed. S.; and Neil E. Grunberg, Ph. D. It provides healthcare workers with frameworks and tools based on the most current research in leadership, psychology, neuroscience, and physiology to help them update or innovate how they lead and build the practices necessary to continue to update their leadership skills. It is provided as a companion to the podcast with Eric Douglas Keene on Diversity Recruiting: Changes and Retention.

I have strong memories of an eye-opening conversation I had with some friends when I began work in a suburban hospital. I met my friend and his wife for a snack at the hospital cafeteria when they visited for his routine physical. I teased him about how nice he was dressed. He looked at his wife and then back at me. He smiled as he replied, “We have to dress up when we go to this hospital,” he said. “Otherwise, the security staff wants to escort us to our physician’s office.” After that conversation, I noticed several instances of African American patients, families, and staff receiving ‘special help’ from the hospital security staff. I was taken aback at both the hospital’s racist institutional behavior and my complete obliviousness to the racism.

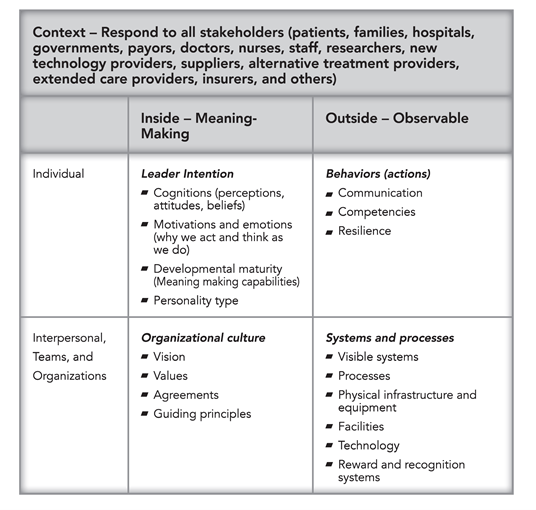

This section is about innovative leadership for JEDI. Innovative leadership for JEDI refers not to STAR WARS mind control techniques, but the other JEDI—[Social] Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion. Innovative leadership for JEDI is the ability to impact individuals, teams, and systems to create a fair and engaging health care organization. For patients. For families. For health care workers. Of all backgrounds, genders, colors, and beliefs. The Innovative Leadership JEDI section is divided into three subsections. Bias and health care, the health care crisis resulting from bias, and a pathway for leaders to address the JEDI health care crisis in their organizations.

Bias and Health Care

Our experiences are that most health care organizations and most health care leaders try to create a welcoming JEDI environment. Most health care organizations and leaders truly value the principles of JEDI. Research and experience, however, reveals too many health care organizations that are unwelcoming and un-inclusive. In the absence of malice, how does a health care organization create an unwelcoming and un-inclusive environment? We submit the answer may lie in cognitive biases that allow organizations and leaders to believe a problem exists, but… “It’s not me and not us.”

Emily Pronin notes, “Human judgment and decision making is distorted by an array of cognitive, perceptual and motivational biases.” Most health care professionals receive training in statistical practices aimed at eliminating biases in clinical practice. Pronin goes on to describe a phenomenon termed blindspot bias writing, “Recent evidence suggests that people tend to recognize (and even overestimate) the operation of bias in human judgment – except when that bias is their own.”

Banaji and Greenwald have further described the blindspot bias as a bias people can readily see in others but have great difficulty seeing in themselves. Blindspot biases manifest in statements like, “I know there is a lot of racial prejudice in the world, but I don’t see color, only people,” or, “I know most people that don’t understand cultural norms can be offensive, but I understand respect, so I am never offensive in any culture.” When someone is aware that a phenomenon regularly exists in others but denies the possibility that it could exist in them, a blindspot bias may be the reason for their confidence. In the health care world, it is often misguided confidence that may dehumanize and disenfranchise others.

In addition to the blindspot bias, health care leaders can suffer from implicit biases. Harvard University’s Project Implicit describes implicit biases as, “attitudes and beliefs that people may be unwilling or unable to report.” Project Implicit provides the example of an implicit bias as, “You may believe that women and men should be equally associated with science, but your automatic associations could show that you (like many others) associate men with science more than you associate women with science.”

Mission statements and Diversity Departments in health care organizations echo a call to deliver the highest possible care and adherence to the value principles of JEDI. This in contrast to the many patients, families, employees, and communities suffering consequences of social injustice, inequity, lack of diversity, and un-inclusiveness. The combination of blindspot and implicit biases create a JEDI crisis in our health care systems. A crisis that hides in plain view through a cloak of “not me, not us” beliefs.

The Tale of a JEDI Health Care Crisis

The evidence on JEDI and health care delivery highlights systemic failures on almost every level. Below are a few health care statistics illustrating the breakdown of principles of JEDI for our patients, their families, and our employees:

- During the first ten months of the Covid-19 crisis, U.S. data from the COVID Racial Data Tracker showed mortality rates 150% higher for African Americans, 135% higher for Indigenous American People, and 125% for Hispanic Americans than for White Americans. Bassett and colleagues reported that African Americans between the ages of 35 and 44 had nine times higher mortality rates than their White American counterparts.

- Marcella Nunez-Smith and colleagues found nearly one in three Black physicians, nearly one in four Asian physicians, and one in five Hispanic/Latino physicians have left at least one job due to discriminatory practices.

- Dickman and colleagues note the top one percent of affluent males live on average 15 years longer than the lowest one percent of poor males. Low-income families are in poor health at rates 15 percent higher than their affluent American counterparts.

- Using U.S. Census Data, The Center for American Progress reports women in the workforce earn $.77 for every dollar their male counterparts earn. Women are often pigeonholed into “pink-collar” jobs, which typically pay less. Forty-three percent of the women employed in the United States are clustered in just 20 occupational categories, of which the average annual median earnings is less than $29,000.

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development reports that female physicians make up only 34 percent of all U. S. physicians.

- More than 25 percent of African American women and nearly 25 percent of Hispanic American women live in poverty. Elderly women have poverty rates over double those of elderly men.

- The Center for American Progress reports more than 10 percent of African Americans and more than 16 percent of Hispanic Americans are uninsured compared to 5.9 percent of White Americans.

- African American adults over age 20 suffer from hypertension at the rate of 42 percent compared to 29 percent for White American adults.

- In a survey of over 27,000 transgender respondents, Herman and colleagues reported, “In the year prior to completing the survey, one-third (33%) of those who saw a health care provider had at least one negative experience related to being transgender, such as being verbally harassed or refused treatment because of their gender identity.”

- A survey of over 40,000 LGBTQ Americans aged 13 to 24 by The Trevor Project found almost half of the respondents engaged in self-harm. And 40 percent have “seriously considered” attempting suicide—in just the past year.

- Ronald Wyatt reports, “The total cost of racial/ethnic disparities in 2009 was approximately $82 billion—$60 billion in excess healthcare costs and $22 billion in lost productivity. The economic burden of these health disparities in the US is projected to increase to $126 billion in 2020 and to $353 billion in 2050 if the disparities remain unchanged.”

JEDI Innovative Health Care Leadership Action

Reading the statistics above and the myriad of statics available, we find it hard to deny a systemic failure of the health care delivery system and our health care organizations. How did it get this bad when we have so many well-intended and highly skilled leaders? Blindspot and implicit biases can cause inaction in an otherwise effective leadership team. Leaders with blindspot and implicit biases do not disregard problems; they render problems moot through the belief, “not me, not us.” We hope the shortlist of statistics above brings some awareness that “me/we” are both the health care problem and the solution.

Innovative health care leaders can change the course of social injustice, inequity, lack of diversity, and un-inclusion. Using their influence, leaders can take an evidence-based approach to JEDI, learn/teach cultural competence, practice cultural humility, create support for diverse populations, and grow communities to change the course of this systemic failure. We elaborate with some definitions and examples below.

Pfeffer and Sutton wrote, “A bold new way of thinking has taken the medical establishment by storm in the past decade: the idea that decisions in medical care should be based on the latest and best knowledge of what actually works.” Pfeffer and Sutton went on to write while the idea of evidence-based care is almost uncontested, physicians only make evidence-based decisions 15 percent of the time. This is certainly of concern for clinical decision-making, and it is an equal concern for changing the tide of systemic JEDI failures.

As leaders, we must ask, “How would someone with a blindspot or implicit bias know if women, minorities, or people of non-traditional identities are experiencing injustice, inequity, or un-inclusion?” The answer is evidence. Do job applicants with the names Julio and Jamal have the same employment opportunities as applicants with the names John and James? Do our women and minority workers make comparable wages to our white male workers? Do immigrant patients feel respected when receiving care? Are our employees reflective of the community in which we reside? We are uncertain without evidence. Without evidence, our instincts and experiences guide us; instincts and experiences which can be skewed by biases.

Innovative JEDI leaders (like you) are actively pursuing evidence that their organizations are socially just, equitable, appropriately diverse, and inclusive. Evidence—accurate data that is analyzed and understood; confirms or denies the existence of JEDI. If a leader does not have JEDI evidence, the “not me and not us” biases may predominate the institutional consciousness.

Cultural learning opportunities should be readily available in your organization. Cultural competence, the ability to recognize, appreciate, and interact successfully with people from other cultures, is essential for any healthcare professional. In addition, Tervalon and Murray-Garcia observed, “Cultural humility incorporates a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique, to redressing the power imbalances in the patient-physician dynamic, and to developing mutually beneficial and nonpaternalistic clinical and advocacy partnerships with communities on behalf of individuals and defined populations.” Innovative leaders teach, support, and model cultural humility within their organizations.

We have had many conversations with health care human resource professionals observing, “We get minority candidates hired, we just can’t get them to stay.” When diverse employees walk into a room with people who do not look like them, do not believe like them, may have preconceived negative ideas about people like them, it can be overwhelming. Patients, their families, and employees need to feel the organization’s support, receive mentoring on the navigation of differences, and understand that their differences are vital for the community and organization’s strength. Innovative leaders forge pathways of support for inclusion, mentorship, and engagement in their health care organizations. Support groups, mentoring programs, organizational messages, and evidence gathering serve to support and retain diverse populations.

Innovative leaders look at the gaps in their communities and think about how to close those gaps. In an article entitled, Physicians for Social Justice, Diversity and Equity: Take Action and Lead, Lubowitz and colleagues note, “Few orthopedic surgeons are minorities or female, and orthopedic surgery is not perceived to be an inclusive specialty. This is an obstacle to equitable diverse hiring.” Despite the lack of diverse candidates in the profession, Lubowitz and colleagues passionately express the need to advocate, inspire, and continuously improve as a profession.

We agree. If there are gaps in finding physicians and other health care employees that are reflective of the community, start programs to recruit, train, and inspire the community. Programs from elementary school to advanced educational grants can all serve to change a community. Lubowitz and colleagues recommend, “In terms of minorities and women making a choice to pursue medicine and then orthopedic surgery as a desired medical specialty, we wield enormous impact and a most direct influence. We must consciously change our behavior and demonstrate that we are an inclusive medical specialty.” Every innovative health care leader can demonstrate support for inclusion.

Most of us have experienced the patient that demands, “I’m sorry, but I don’t want a [Female, Jewish, Muslim, Gay, Old, Younge, Black, Hispanic, Other] physician. This is my health, and I cannot afford to be politically correct.” As if unsubstantiated biases are merely politeness. Prejudice can be malicious hate or blindspot and implicit biases. In any form, a lack of JEDI weakens the health care delivery system causing pain and suffering for the community. Effective innovative leaders replace, “Not me, not us” with, “It could be me; it might be us” to ensure health care teams, organizations, and communities are just, equitable, diverse, and inclusive.

About the Author

Maureen Metcalf, Founder, CEO, and Board Chair of the Innovative Leadership Institute is a highly sought-after expert in anticipating and leveraging future business trends to transform organizations. She has captured her thirty years of experience and success in an award-winning series of books that are used by public, private, and academic organizations to align company-wide strategy, systems, and culture with innovative leadership techniques. As a preeminent change agent, Ms. Metcalf has set strategic direction and then transformed her client organizations to deliver significant business results such as increased profitability, cycle time reduction, improved quality, and increased employee effectiveness. She and the Innovative Leadership Institute have developed and certified hundreds of leaders who amplify their organizations’ impact across the world.

Photo by Piron Guillaume on Unsplash