The Courage to Assume Responsibility

Ira Chaleff is an author, speaker, workshop presenter, and innovative thinker on the beneficial use of power between those leading and those following in any situation as a companion to his interview with Neil Grunberg, Ph.D., a Professor of Military & Emergency Medicine at the Uniformed Services University, Courageous Followership. This interview is part of the International Leadership Association Series. This series features guests from the International Leadership Association 2022 Global Conference held in Washington, D.C., in October 2022.

An excerpt from chapter 2 of The Courageous Follower:

THE MOST FREQUENT COMPLAINT I hear from leaders is that they would like the members of their team to assume more responsibility for the organization and initiate ideas and action on their own. While there are often very good reasons team members don’t do this, embedded in either the leader’s style or the organizational culture, it is interesting to hear that most leaders want their staff to take more initiative. They don’t want to be the only one leading. Recent research on courageous follower behaviors shows that, although each of the behaviors is valued, the courage to assume responsibility is as valued by leaders as the other four behaviors in the model combined. Examining our preparedness to exercise this responsibility is a crucial platform for moving toward partnership with a leader.

When I was at the University of California at Berkeley in the early sixties, a confrontation between the police and students erupted over the subject of free speech. The confrontation happened in the student plaza while the ad hoc student leadership and the administration negotiated the issues elsewhere. I was one of the hundreds of followers supporting the student leadership. By nightfall hundreds of police and thousands of students on both sides of the issue had amassed. The atmosphere was growing ugly, with stink bombs and epithets being hurled at the demonstrators. It looked like the helmeted police would charge into the demonstrators to break up the sit-in. The crowd included a person who was blind and children. I was concerned that people would be hurt.

Joan Baez, the folk singer and political activist, was performing at the Greek theater on another part of the campus that evening. She had recently achieved national fame. I called the hotel where celebrities stay in Berkeley and left her a message describing the situation. I asked her to come to the site of the confrontation, expressing the hope that by having a prominent figure present more restraint would be exercised and violence could be prevented. Though she didn’t know me, she responded and appeared a little while later. While she made her presence known, each side restrained itself until a settlement was reached and everyone voluntarily dispersed. I learned the power of taking initiative without formal authority.

Unfortunately, I have not always assumed that much responsibility. Recently, I found myself disappointed by the quality of meetings my company held. The meetings consumed a lot of expense and time as people came from two continents, yet they seemed to cover the same ground each year in an uninspiring format. I complained about it to the organization’s founder and president but did nothing else to change it.

Then I had the opportunity to use a self-assessment instrument and was startled to find how disaffected I had become with the president. This flew in the face of my self-image as a positive, contributing team member. I was challenged to assume responsibility for the situation rather than complain while it deteriorated.

I drafted a memo to the other participants in the company meetings and told the president that I intended faxing it to each of them. He supported the initiative. The memo explained what a terrific opportunity I saw in our annual meetings and offered a creative idea for taking better advantage of the meetings. I asked for their feedback. Nearly all replied, several with ideas of their own that I felt improved on mine. Out of this process, and to the president’s delight, we constructed a new, stimulating, and valuable format for part of the meeting.

By assuming responsibility for our organization and its activities, we can develop a true partnership with our leader and sense of community with our group. This is how we maximize our own contribution to the common purpose. Assuming responsibility requires courage because we then become responsible for the outcomes—we can’t lay the blame for our action or inaction elsewhere.

But before we can assume responsibility for the organization, we must assume responsibility for ourselves. I had to recognize my disaffection and do something to change it. I had to assume responsibility for my own growth. We cannot remain static ourselves and expect to improve the organization.

In this chapter, I explore the responsibility a courageous follower takes for self-development and for the development of the organization. Though we coordinate our activities as appropriate, we also take actions independently of the leader to forward our common purpose.

SELF-ASSESSMENT

Assuming responsibility for our personal development begins with self-examination. We cannot know in which direction we need to grow until we first know where we are. Courageous followers do not wait for performance reviews (strained events that these usually are anyway); they assess their own performance.

In addition to evaluating their job “competencies,” courageous followers also examine the more illusive subject of their relationships with teammates and leaders. If charity begins at home, development in the relationship between followers and leaders begins in a follower’s vestibule; a follower’s issues with authority are the other side of a leader’s issues with power.

Our relationship to authority is so deeply ingrained that it is difficult to be fully aware of our beliefs and postures vis-à-vis leaders. For our entire childhoods, at home and school, those in authority had tremendous power to dictate to us. We learned to survive by complying with, avoiding or resisting those authorities. The strategies we adopted became patterns for future behavior and influence our attitudes toward our current leaders.

Most work environments in adulthood reinforce our childhood relationship to authority. We must strive for greater awareness of our own beliefs, attitudes, and patterns of behavior toward authority, and look at their consequences. For example:

Challenging a specific leader on a specific subject may be healthy, but a pattern of challenging all leaders on all subjects is not. A rebellious, alienated follower will never earn the trust to meaningfully influence a leader

A follower’s deferential language and demeanor toward a leader may be appropriate, but strained subservience or chronic resentment are not. A follower who is too subservient and eager to please authority cannot provide the balance a leader requires to use power well.

Clamming up when a leader interrupts us in a raised voice may have been necessary at home or school, but it serves us and the leader poorly now. Tolerating disrespect for our voice and views will reinforce the behavior and weaken the relationship.

It is important to move beyond viewing a leader as a good parent or bad parent, a good king or bad king, a hero or villain in our world. If we become aware of such attitudes, our challenge is to learn to relate to the leader on a different basis. By paying attention to how we interpret the leader’s actions, to the feelings that interpretation evokes in us, and to the behaviors we employ to cope with those feelings, we can loosen our grasp on the mechanisms we once needed for survival. We can begin to examine what other choices we have as adults for relating effectively to authority.

FOLLOWERSHIP STYLE

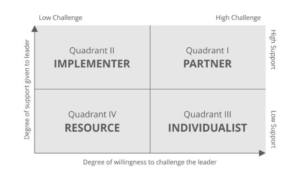

There are different ways to represent our individual style of relating to leaders. Useful models for doing this can be found in the works by Robert Kelley and Gene Boccialetti, cited in the bibliography. In my workshops, I use a two-axis representation derived from the core of the Courageous Follower model that participants in workshops find helpful in understanding their strengths and potential growth needs.

The two critical dimensions of courageous followership are the degree of support a follower gives a leader and the degree to which the follower is willing to challenge the leader’s behavior or policies if these are endangering the organization’s purpose or undermining its values. This holds true at all levels of leadership and followership. We will examine both of these dimensions in depth in subsequent chapters. At this point, however, it is useful to reflect on where you place yourself in this matrix of follower behaviors.

The possible combinations of these two dimensions produce four quadrants that can depict the posture you tend to assume in relation to leaders. There is variance, of course, depending on the leader to whom you are relating. But, if you change quadrants radically based on the leader’s temperament and style, you are ceding too much power to the leader to determine your professional behavior. It is useful to identify your core tendency or natural position in relationship to authority at this point in your personal development. Then you can chart a growth path for yourself.

The four possible quadrants in this model of followership style are

- Quadrant I: high support, high challenge

- Quadrant II: high support, low challenge

- Quadrant III: low support, high challenge

- Quadrant IV: low support, low challenge

QUADRANT I: HIGH SUPPORT, HIGH CHALLENGE – THE PARTNER

A follower operating from the first quadrant gives vigorous support to a leader but is also willing to question the leader’s behavior or policies. This individual could be said to be a true partner with the leader and displays many of the characteristics identified with courageous followership in this book. Even within this quadrant, of course, there is room for growth as one can become stronger and more skillful in both dimensions.

QUADRANT II: HIGH SUPPORT, LOW CHALLENGE – THE IMPLEMENTER

This is the quadrant from which most leaders love to have their followers operate. Leaders can count heavily on followers who operate from this profile to do what is needed to get the job done and not require much over sight or explanation. However, if the leader begins to go down a wrong path, these are not the followers who are likely to tell the leader so or, if they do, they are not likely to pursue the matter if the leader rebuffs their attempts. Growth for those tending to this style of followership lies in the direction of being more willing to challenge a leader’s problematic actions or policies and learning to do so effectively and productively.

QUADRANT III: LOW SUPPORT,HIGH CHALLENGE – THE INDIVIDUALIST

Surrounding every leader are one or two individuals whose deference is quite low and who do not hesitate to tell the leader or anyone else in the group, exactly what they think of his or her actions or policies. These are potentially important people to have in the group as they balance the tendency of the rest of the group to go long with what seems acceptable while harboring reservations. However, because these individuals do not display equal energy in supporting the leader’s initiatives, they marginalize themselves. Their criticism becomes predictable and tiresome, and the leader finds ways to shut them out. Growth for individuals who operate from this style of followership lies in the direction of increasing their actual and visible support for the leader’s initiatives that forward the common purpose.

QUADRANT IV: LOW SUPPORT, LOW CHALLENGE – THE RESOURCE

Any group has a certain number of people who do an honest day’s work for a day’s pay but don’t go beyond the minimum expected of them. There are often legitimate reasons for this. They may be single parents whose priority is leaving at 3:30 to pick up their children from day care, graduate students whose priority is excelling in their course work or volunteers who can give only a few hours a week. However, it is difficult to advance their careers or make significant contributions to the organization while operating from this quadrant. When they are ready to give more priority to their participation in the group or organization, they must begin to raise their level of support for the leader and begin to earn the standing to also credibly challenge policies and behavior.

The following is a summary of the attitudes and behaviors likely to be displayed by individuals relating to leaders from each of these quadrants.

While these tendencies can be measured, you probably already have a sense of how you tend to operate, at least in relationship to the current leaders with whom you interact. As you read further, keep in mind this self-assessment and the direction in which you feel you would like to grow. You can then consider and test the ideas and suggestions you will encounter to help you do so.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Ira Chaleff is an author, speaker, workshop presenter and innovative thinker on the beneficial use of power between those who are leading and those who are following in any given situation. His groundbreaking book, The Courageous Follower: Standing Up To and For Our Leaders, is in its third edition, has been published in multiple languages and is in use in institutions around the globe including educational, corporate, government and military organizations. He is coeditor of The Art of Followership: How Great Followers Make Great Leaders and Organizations, part of the highly regarded Warren Bennis Leadership Series. He has written on the appropriate use of power in non-traditional settings in his creative non-fiction work, The Limits of Violence: Lessons of a Revolutionary Life. He holds a degree in Applied Behavioral Science and is a Board Certified Coach from the Center for Credentialing and Education. Ira Chaleff lives in the beautiful Blue Ridge Mountains outside of Washington, DC, where bears frequently disobey the No Trespassing signs on the road and help keep his connection strong with the wonders of nature.

Neil E. Grunberg, Ph.D., is Professor of Military & Emergency Medicine at the Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland. He is a medical psychologist, social psychologist, and behavioral neuroscientist. Dr. Grunberg earned baccalaureate degrees in Medical Microbiology and Psychology from Stanford University (1975), a Ph.D. (1980) in Psychology from Columbia University; and completed doctoral training in Pharmacology at Columbia’s Medical School (1976-79). He has been educating physicians, psychologists, and nurses for the U.S. Uniformed Services since 1979 and has published > 220 papers addressing behavioral medicine and leadership. In 2015, Dr. Grunberg was selected to be a U.S. Presidential Leadership Scholar.

RESOURCES:

Ready to measure your leadership skills? Complete your complimentary assessment through the Innovative Leadership Institute. Learn the 7 leadership skills required to succeed during disruption and innovation.

- Follow the Innovative Leadership Institute LinkedIn page

- Subscribe to Innovating Leadership and listen on your favorite podcast platform

- Subscribe to our blog – Insights

Check out the companion interview and past episodes of Innovating Leadership, Co-Creating Our Future via Apple Podcasts, TuneIn, Stitcher, Spotify, Amazon Music, Audible, iHeartRADIO, and NPR One.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!